Why “Whitworth”? Whitworth Park is named after Sir Joseph Whitworth (1803-1887), best known for his standardisation of screw threads known as British Standard Whitworth. He made clear before his death that he intended to devote most of his fortune to public, and especially educational, purposes but died without completing any scheme. After making arrangements for his wife and other charitable and personal legacies, he bequeathed the remainder of his estate to Lady Whitworth, Richard Copley Christie and Robert Dukinfield Darbishire to use, “they being aware of the general nature of the objects which I should myself have applied such property”. It was his friend and solicitor, Darbishire, however, who led this task with great tenacity. Whilst enabling many projects in and around Manchester, his special interest was to make possible an institution that would make available the experience and understanding of art as well as meeting the demand for a public “pleasure ground”, and the Whitworth Park and Institute was opened in 1890, three years after Joseph’s death.

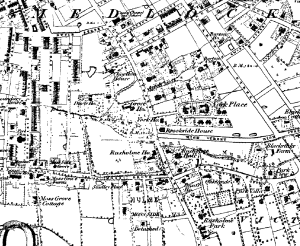

Why here? This part of Manchester in 1884 was very different from what we see now but changing rapidly. Chorlton-on-Medlock had been incorporated into the city in 1838 and had a tightly packed population of over 55,000. Moss Side grew rapidly from isolated houses in the early eighties to a population of 20,000 by 1884, but remained outside of Manchester until 1904. The population of Rusholme, however, mainly well to do merchants and professionals trading in the city, grew less quickly, only amounting to about 8,000 people when it was incorporated in 1885. So the total population of the three districts was more than 80,000. This was the period during which the value of open space was increasingly being appreciated as an antidote to the cramped and poorly ventilated living accommodation, poor public health and harsh working conditions which were common in the rapidly developing city. Alexandra Park, which had opened in 1868, was the only park in the area and was considered in the mid 1880’s to be too far from the most congested areas be benefit the residents.

The Potter Estate. Edmund Crompton-Potter (uncle of Beatrice Potter) owned and lived in Rusholme House (built around 1810), which stood on the corner of Moss Lane East and Wilmslow Road. His estate spanned Rusholme Brook, which separated Rusholme from Chorlton-on-Medlock and included Grove House,(built about 1830) and an area called “Potter’s Field”, in total 20 acres. Both houses had extensive gardens laid out and maintained with care. Darbishire was also named executor in Crompton-Potter’s will, and when he died in 1884, made arrangements to sell the whole estate of 20 acres, as a whole or in parts. However the lot was withdrawn when no acceptable offer was made at the auction. There was considerable correspondence in the Manchester Guardian, recording well attended public meetings debating the case for the City Council acquiring the Potter Estate for a public park. It was felt by some that the land would otherwise be acquired by builders for 400-500 additional houses, exacerbating the growing problems arising from increasing population density. But others were more wary of the motives of people living in the only recently incorporated Rusholme area. A petition to the Council was nonetheless raised but failed to gain sufficient support in the Council and for a period there was no movement recorded in the newspapers although correspondence continued to make the case for a public park. In the meantime Darbishire opened the garden of Rusholme House and Potter’s Field to the public, who turned up at weekends in their thousands, on occasion being entertained by a brass band!

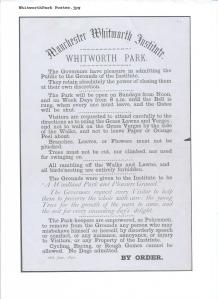

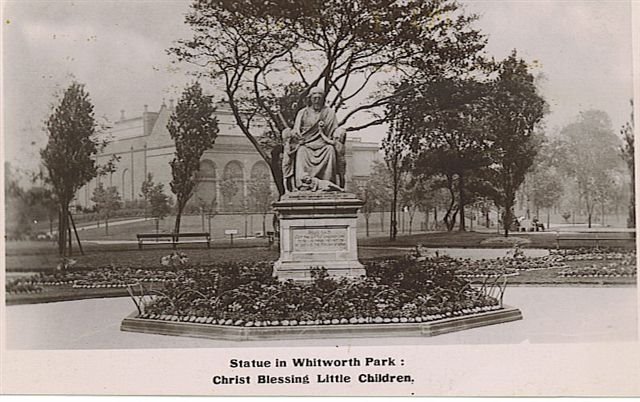

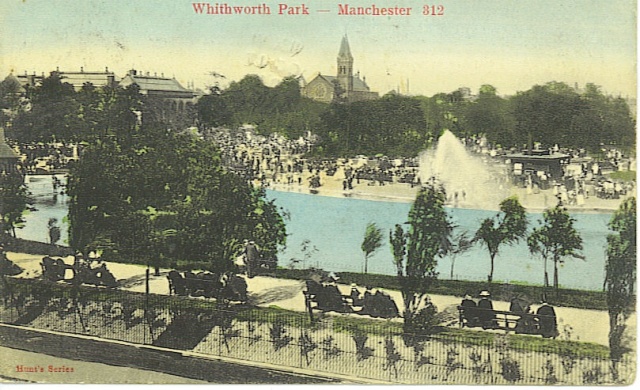

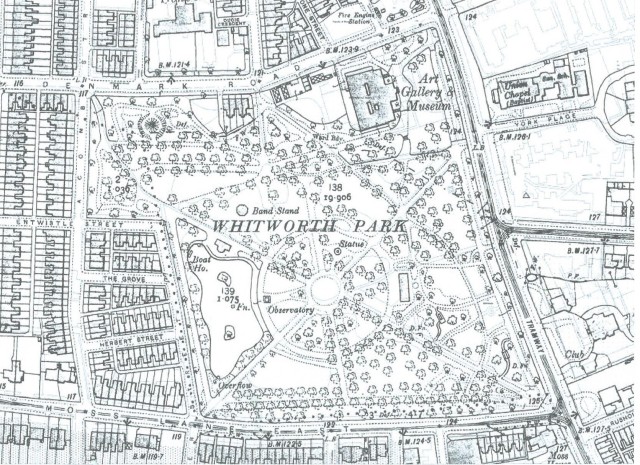

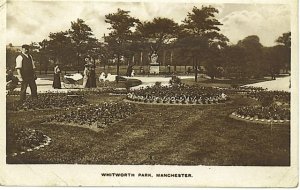

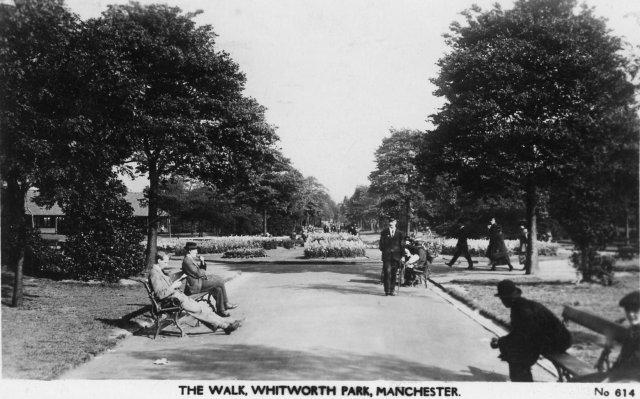

The making of the Whitworth Institute and Park. Whitworth’s death, in January 1887, appears to have opened up this situation. His legatees bought the estate for the Whitworth Trust at about the original asking price. An offer was made to give the land conditionally to the city for a public park subject to the council also building educational establishments including an art gallery. However it was the Trust which demolished Rusholme House, installed drainage and, after sending Alfred Wilsher, park superintendent, to the continent to see examples there, re-laid its garden, Potter’s Field and the grounds of Grove House as an organised Park with wide avenues, new trees and flower beds, a bandstand and shelters, and later a lake with large fountain, islands, boathouse and pavilion. Rooms in Grove House were re-organised to accommodate a growing collection of sculpture and paintings and on 16 June, 1890 the Whitworth Institute, which had been incorporated in 1889, quietly opened Whitworth Park to the public as “a woodland park and pleasure ground”, the event being marked by a public notice on the gate and in newspapers but no formal ceremony. The Park was very popular and attracted large numbers of people and work continued to add to its attractions. An observatory to record meteorological data was added by Owens College next to the lake in 1893 and in 1895 Darbishire donated a sculpture by George Tinworth, Christ blessing the Children.

This was, apparently, the first sculpture erected in a Manchester Park. Band concerts were a regular feature. In the meantime the Whitworth Institute, emboldened by generous donations following its incorporation, was making plans to improve accommodation for its growing art collection and in 1891 an architectural competition to rebuild Grove House as an Art Gallery, was won by J.W.Beaumont, a Manchester architect already involved in other projects managed by the legatees, including probably the design of the buildings in the Park. The rear part of Grove House was demolished to make way for new galleries built to the winning design between 1892 and 1898.

The Lease to the Council.

Although the Park was very successful, the cost of its development and maintenance was inhibiting the completion of Beaumont’s scheme, and in 1904, the Park was leased to the City Council for 999 years in exchange for a small annual rent. The Institute retained Grove House and about two acres of the original 20 acre plot, with an option to develop an additional area subject only to three months notice.

The handover was effected with considerable ceremony in a special meeting of the City Council followed by an event in the Institute, all heavily reported in the newspapers of the time. Release from the burden of the Park enabled the Institute to embark on the rebuilding of its front and final part of Beaumont’s design and this was opened in 1908. Although Darbishire died shortly afterwards, his contribution to late 19th and early 20th century life in Manchester had earned him the freedom of the city in 1899. His obituary in the Manchester Guardian describes a man of an independent and non-conformist nature who pursued his interests and objectives with great tenacity, who donated his collections to public institutions and found ways to promote and enable many good causes. His papers wee, on hos instructions, destroyed on his death so we are denied what would have the background to a fascinating record.

Separation of Park and Gallery.

The terms of the lease required that the Institute erect a fence to mark the limit of the leased area and separate entrances made to the Gallery and Park . The new entrance to the Park was made opposite that of St. Mary’s Hospital which had been opened by King Edward VII in 1910, not long before his death. A monument by John Cassidy to the king was raised in 1913 immediately inside the gates which were furnished after the 1914-8 war with stonework piers and elaborate wrought iron gates,

The Park’s original features.

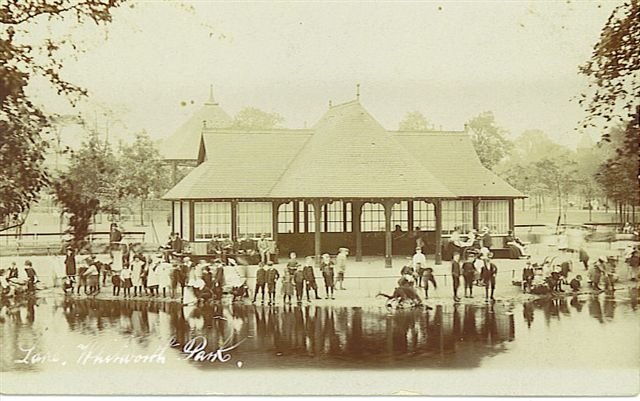

The Lake, originally had two islands and a large central fountain and there were boating trips from a boat house in the north west corner. As the Park developed there were a number of changes. The fountain along with the islands and the boat house was removed in 1923 and paddling, which may previously have been restricted to the area immediately in front of the pavilion terrace, together with the sailing of model yachts was encouraged. In 1929 a “work scheme”, in response to the economic situation at the time, enabled the lake to be cleaned out and concreted at a depth more suitable for paddling. The Whitworth Park Community Archaeology and History Project 2011-13 uncovered lots of evidence of this work including a wide ranging collection of objects lost in the lake over the intervening period. This material with background material about the use and development of the Park was exhibited in a public exhibition, “Pleasure, Play and Politics in Whitworth Park” held in the Manchester Museum between May and October 2014.

The Lake Pavilion, probably designed by Beaumont, was a finely detailed rectangular timber structure with a projecting open semi-circular bay, all capped with a steeply pitched, hipped roof reflecting its complex shape. The roof was covered in red tiles, reflecting the red shale covering many of the paths around the Park. The pavilion’s central division and outer walls each had seats facing both ways, the walls with glazing above. On the lake side there was a wide crushed stone terrace, sloping down to the water which was edged with multiple rows of stone sets and an asphalte lake edge. A few feet from the water was a low iron fence presumably to make the limit of paddling area. Large calcite stones were set into the terrace as features (perhaps as rough seats) here and around the lake edge. Apart from the lake edge detail the 2011-13 archaeology found little of the remains of the pavilion.

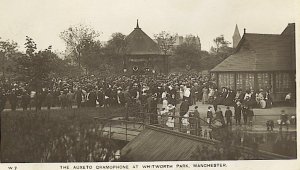

The Bandstand, designed with similar details to the pavilion, was an octagonal timber structure, raised on a brick plinth so as to be more visible to the public. It also had a high red tiled roof. It stood in an enclosure probably surfaced in crushed stone and was surrounded by young trees which still remain (but as mature trees), although the bandstand does not, having been removed with other remaining structures in the 1950’s. The band concerts were a particular interest of Darbishire, who had pioneered the idea in Potter’s Field before the Park was laid out. There was considerable debate in the City Council after they took over the Park as to the correctness of having concerts in parks, particularly on Sundays, and later correspondence in the Guardian about the quality of the music. However, their popularity with the general public was not in doubt and steps were taken to capitalize on this by enclosing the immediate area near the bandstand and charging for chairs. There were experiments with orchestral and choir concerts and even community singing but these seem not to have been particularly successful. In the first World War the programmes were devised to be uplifting and similarly morale boosting events and exhibitions were held in the Gallery. The octagonal brick foundation to the bandstand was uncovered during the the archaeological digs in 2011 and 2013.

The observatory and weather station (on the right) with bandstand and pavilion behind. (Courtesy Bruce Anderson)

The Observatory readings were collected daily by people from Owens College (now the University of Manchester) and published in detail on the Park notice board as well as in the Guardian and other newspapers together with articles on any “extraordinary” weather, “10 hours of sunshine” in March 1926 and “skating on the ice” in January 1933. The building and its instruments, however, were unfortunately irresistibly attractive to unruly children and there are constant references to damage and loss.

The Shelter was a long rectangular building on the Oxford Road side of the Park, built and laid out using similar design details and materials as the Lake Pavilion. It can be seen through the trees on the left hand side of the picture below.

The Path from Greenheys to Rusholme with the centre circle in the middle ground. The Shelter is behind the trees to the left.(Courtesy Bruce Anderson)

The Paths

The main paths were laid out, 6 metres wide, in a simple diagonal pattern linking the four corners of the Park with a circular central feature where they cross. Similar wide paths ran parallel to the perimeter and between them and the centre was a less wide circular path . There was also a network of secondary paths. The paths were edged with three rows of blue bricks as a gutter, backed by a tile providing an upstand to the grass edge. The smaller paths were topped with red shale. The archaeology in 2011 exposed one such path in the present play area with edge bricks and drainage in good condition. It had been covered with topsoil during later alterations.

The Park post 1904. Reports in the Manchester Guardian in years up to and including the 1930’s as well as recording a concern about costs of, and returns from, the attractions in the Park, regularly record comments on its band concerts and other musical offerings which were well attended. In 1912 a demonstration of the Auxeto gramophone from the bandstand attracted an enormous crowd not all of whom, according to reports, were impressed by the recorded performance!

The character of the Park was described in the 1915 report to the Council by the Park Superintendant as being notable for its trees and flowers rather than the tennis courts and playgrounds characteristic of other city parks and this is reflected in the number of regular articles and letters in the Manchester Guardian of this period and up to the 1930’s. Many of these articles are by W. Pettigrew, Parks Superintendent for a long period, and an influential character in this field in the city.

The War Memorial. The first world war saw the Park and Institute used for morale boosting activities and exhibitions as well as being a local focus for recruiting campaigns across the city. The nearby Ducie School was used as a military hospital and the Park used for recreation. There is regular reference in letters to the Guardian between 1905 and 1929 to the use of the shelter nearest Oxford Rd by “invalided men” and men “past work”. It appears the building was used as a refuge where people smoked, played cards, and even held lectures and debates, and there were requests first of all to keep it open past Park closing time in the winter and then to add heating and advertise it as a “Soldiers Room”. This pressure eventually bore fruit in 1929 When a coal stove was added and the shelter at least partially enclosed. It remained, however, subject to normal park closing times. However, the connection of the Park with the military, is perhaps confirmed by the approach in 1933, by representatives of the 7th Battalion Manchester Regiment for sanction to erect a war memorial. The battalion was one of three Territorial Army units located in the city and Whitworth Park lay within its recruiting area. They had been mobilised in 1914 immediately prior to the outbreak of war and fought at Gallipoli and in the battles on the Western front in France and Belgium. A memorial to those killed in action was built into a wall at the drill hall on Burlington Street. However this building was sold in 1921 following the amalgamation of the 7th with the 6th Battalion and the memorial was lost. The surviving members, however, considered that a permanent memorial was necessary and following a competition organised by the Chair of Architecture at the University, Prof. AC Dickie, Norman Wragge’s design was selected and built. The 7th was reformed in 1939 and served in North West Europe, ending the war in Bremen before final disbandment. The Manchester Regiment Museum is in the Town Hall at Ashton-under-Lyne.

The Changing Background.

By the mid 1920’s the Park’s surroundings had changed. The tightly planned earlier housing on its north and east sides had been largely replaced by the developing University and Hospitals but a very large residential population had grown on its west and south sides. Whilst this local population was good and regular reports in the newspapers of new and changing attractions sustained the Park through the 1930’s, the Gallery was less successful. By 1931 annual visitor numbers, which had reached 176,865 in 1917, declined, and income was not meeting cost. Its treasurer appealed for help to its Friends group to find money even to do essential repairs. Despite the determined and imaginative management by Margaret Pilkington, who gave her services as Honorary Director for over twenty years, this decline continued through the 30’s and did not get above 50,000 again until the mid 1980’s.

The Second World War. By the end of the 1938 preparations were being made across the city to protect its people against air raids in the anticipated war and the Denmark Road side of the Park was one of the sites chosen for trench type shelters. The “Manchester blitz” in December 1940 resulted in the loss of a number of houses near to the Park and the Gallery basement was made available during this period as a temporary refuge for people bombed out of their homes. Morale boosting activities and entertainments were held in the Park and its buildings used for fire fighting demonstrations. Barrage balloons were located in the Park throughout the war and an accident involving the cables for one of these is believed to be the cause of damage to Tinworth’s sculpture “Christ blessing the Children”. The sculpture was removed into storage and apparently lost.

Decline of the Park. By 1947 the condition of the buildings and lake was deteriorating to a critical stage and in the lake had been drained and the “lawns” described in a Guardian report as “threadbare”. There are regular reports of damage to the Observatory but photographs from the period show that flower beds were still being planted and maintained. This was against a background of national and local planning for the reconstruction of the country following the devastation of the war. The Manchester Plan of 1947 included for an extensive centre for medicine, learning and the arts built around a developed road system and including a greatly enlarged Whitworth Park. Such planning, whilst never implemented as a whole, influenced the relatively piecemeal development of successive Manchester Education Precinct plans and the development of the Manchester Hospitals campus.

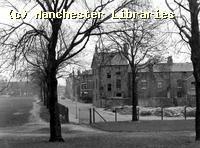

Demolition of houses on west side of Park 1970. Notice lake filled in on left of picture and paths lost.(Courtesy Manchester Libraries)

The perceived need was to accommodate the pressures arising from the growth of motor traffic, the need for better housing and planned national investment in health and education. Large areas of “sub standard” housing were cleared in the name of “comprehensive development” which was intended to produce integrated housing developments associated with schools, health centres and shops and served by a rational circulation system fed by arterial and feeder roads. The plans for Manchester included large areas in Moss Side and Hulme, and plans for the demolition of relatively good housing were strongly contested by local residents, but to no avail, and much of the artisan housing immediately next to the Park was demolished in the late sixties and early seventies to be replaced by schools and industry. This period of change, resulting in a reduction of the Park’s nearest likely users, together with a changing and transient population mix, exacerbated the effect of the council in the late 195o’s filling in the lake and removing its pavilion, observatory, bandstand and a number of circulatory paths , presumably seeing the old features as insufficiently relevant to modern society to justify the expense of maintenance and repair.

Residents from that time remember that the Park,and even some of the streets, were considered dangerous and maintenance was further reduced following the government’s reductions in local authority budgets in the 1980’s and 90’s. Local residents petitioned against the loss of amenity but remedial measures, including a new playground, were vandalised and abandoned and the Park deteriorated rapidly, gaining a reputation (particularly in the local news media) for anti-social behaviour, muggings, assault and even rape and murder. New University students were advised by the police against using the Park.

Oxford Rd path, cycleway and isolated grass strip outside new fence. Note the loss of the Main Entrance.(photo Ken Shone)

This unsatisfactory situation was not helped by the Oxford Road perimeter walk being effectively separated from the body of the Park when this footpath was later designated one of the main cycle routes into the city. The main entrance to the Park was removed and later still the addition of a new fence isolated the strip between this and the bus stops, making maintenance difficult and therefore sporadic and inadequate, further adding to the impression of neglect. The amount of cycle traffic at peak times created regular problems for both pedestrians and cyclists sharing this path.

Much of this unwanted catalogue of change arose from the unique position of the Park, standing at the beginning of the Oxford Road Corridor and at the place where large residential, academic and medical populations meet the ebb and flow of traffic, wheeled and pedestrian, into the city centre. Such a location will always be a place where people gather as demonstrated by the Park’s popularity in the pre-WW2 years. But the lack of accommodation for the Park in the planning of the great changes in its surroundings, and the apparent tendency to leave it for some other “plan” to deal with, left the Park without a role or support just when its original features and attractions needed support and attention. Such considerations, though, are not material to demonstrations and rallies and certainly in the seventies and since, its location made the Park a natural choice for a wide range of campaigns.

Decline and rebirth of the gallery. Against this background the gallery continued to struggle through the period after the war. It was in a strange position. It had, by 1950 , through the efforts of Margaret Pilkington and her sister Dorothy, and a number of important gifts and bequests, built up a collection of international importance but yet there was no money to keep and maintain the building. The Governors were selling works of art to meet current expenditure. The University was approached , and after a number of legal difficulties arising from the original Institute being set up by Royal Charter, the Gallery was handed over in 1958. Margaret Pilkington became Deputy Chairman of the Board of Governors and a new director, John White, assisted by Francis Hawcroft, appointed. The University quickly made the decision to remodel most of the Gallery and architect John Bickerdike was appointed to this task. His vision was to retain the Edwardian shell but remodel the interior in accordance with contemporary ideas. The results of this work were well received. In particular, the changes to the opening up of large windows in a previously blank wall in the South Gallery, gave views of the Park for the first time since the Beaumont scheme was built. Other galleries were named, in recognition of great contributors, the Darbishire Hall and the Pilkington Gallery, whilst the Gulbenkian Gallery gave recognition to the financial help given by this foundation. The completed reconstruction was formally opened in 1968 and visitor numbers increased so that as the centenary of the Gallery drew near in 1988, the Director at the time, Prof CR Dodwell, announced a new Appeal, under the patronage of the Prince of Wales, for monies to fund a new extension.

Regeneration.

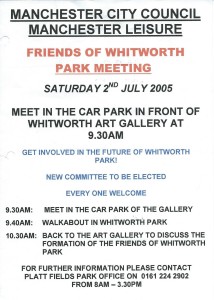

So, about hundred years after the City had relieved the Whitworth Institute of the burden of the Park, it was itself looking for ways to reduce the cost of its non-statutory services. What had been seen as a source of civic pride had become an eyesore as problems of maintenance and funding had led to decline and neglect. A proposal was made to build a “temporary car park”, involving the removal of trees, high fencing and lighting, to serve the growing number of people visiting the hospitals. This was ill judged – local councillors had been given no prior warning and they, together with large numbers of others objected and the suggestion was hastily withdrawn.  Following this, Alistair Smith, the new Director of the Gallery, approached the Friends of the Whitworth in 2004 for support in meeting representatives of the Parks Department and Councillors to discuss a more positive future. He presented the outline proposals that had been drawn up by architect Ahrends, Burton and Koralek for the Gallery’s proposed extension, which showed a stronger engagement with the Park. Meetings with local residents followed and in 2005 agreement was reached to set up a Friends group for the Park.

Following this, Alistair Smith, the new Director of the Gallery, approached the Friends of the Whitworth in 2004 for support in meeting representatives of the Parks Department and Councillors to discuss a more positive future. He presented the outline proposals that had been drawn up by architect Ahrends, Burton and Koralek for the Gallery’s proposed extension, which showed a stronger engagement with the Park. Meetings with local residents followed and in 2005 agreement was reached to set up a Friends group for the Park.

Development agreements entered into by developers of nearby apartment buildings had produced money that could be used by the council for improvements to the Park and the new group was asked for suggestions. It was agreed that a redefinition of the Park, with renewed fences and gates was the first step to be followed by proposals by the Friends for a longer term strategy based on subsequent tranches of money from this source contributing to the repair and renewal of the Park’s infrastructure, rather than piecemeal development of one-off features.

The guidelines for this strategy, which the Friends had set out in a document called “Towards a Development Plan”, were taken from the criteria of the Green Flag Award, which had been developed in 1966 to encourage the provision of good quality public parks and green spaces that are managed in environmentally sustainable ways. This led to the Friends working with the Park Manager to produce the first comprehensive Management Plan for the Park 2011-16, which was finally produced in 2010. Since that early co-operation, money arising from the development of over 2000 apartments within five minutes walk of the Park, has enabled good progress to be made so that by the Spring of 2015 the main infrastructure will have been repaired and furnished and new attractions added .( “Projects“).

This work, together with a much better grounds maintenance regime, transformed the public perception of the Park and local workers, students and residents are now comfortable about spending leisure time there, enjoying the green space and the trees. Another aspect of the Plan, is Community Engagement, and rebuilding a “park community” from its disparate and transient elements in the surrounding residential, academic and hospital areas has been a slow process, but a large number of volunteers and schoolchildren were involved in the Community Archaeology and History Project, led by the University’s Archaeology Department and funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund, over three years between 2011 and 2013. Two “digs” in the lake and bandstand areas and unearthed a great deal of artifacts illustrating people’s use of the Park in its heyday.

Through the process of archaeology and observation and discussion about the results, we learned about the character of the original park and the lives of its users. This was backed up by archival research and the collection of people’s memories and the product of the whole project was presented in an Exhibition in the Museum in the summer of 2014.

Meanwhile, the council was revising its approach to park maintenance. It had been accepted for some time by environmentalists that the practice of gang-mowing on a regular basis, and the loss of shrubberies etc reduced parks to ecological deserts with a corresponding reduction in capacity to support wildlife. In the context of the global loss of species this was not sustainable, and from 2010 a reduced mowing regime was introduced which met both the need to reduce costs and the need to increase biodiversity.

So when the council reduced the mown areas in Whitworth Park, the Friends group arranged that the so called “environmental areas” were located on the perimeter and that paths be cut through the un-mown areas to re-establish perimeter walks lost in the changes implemented in the fifties. These add variety and attraction to walks around the Park as spontaneous growth of a wider variety of plants and grasses becomes more evident. Staff and students volunteered to help the Friends on tasks mainly directed towards maintenance and planting in these peripheral areas of the Park and the improvement in the Park was sufficient by 2012 to gain a Green Flag Award indicating that in the opinion of the visiting judges it had reached the national standard. This was repeated in 2013 and 2014 and in the latter year a submission to the RHS Britain in Bloom “It’s Your Neighbourhood” scheme gained the Friends a silver-gilt award for the Centre Circle, which was designed by and maintained by the group.

The Gallery in the Park.

The gallery was also changing. The development initiative announced by Prof. Dodwell in 1988 and followed up by Alistair Smith in the 90’s and early new century, had failed to get sufficient backing to allow an application to the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF). In 2007, following the unification of the University and UMIST and the appointment of a new Director, Maria Balshaw, the gallery renewed its bid to extend into the Park. Visitors had grown from 86,000 in 2006 to 139,000 in 2008 as a result of the expansion of the public programme, learning and family programmes. The fence between the gallery and the Park was removed and a sculpture, Whitworth Obelisk, by Cyprien Gaillard, erected on the base of the lost “Christ blessing the Children”.

The funds raised by the Friends of the Whitworth for the earlier scheme, together with renewed and more positive interest from the new University, enabled a competition organised by RIBA to be run in 2009 for the design of a “Gallery in the Park”. The competition brief was prefaced by a quotation from Margaret Pilkington, who, following a visit to Oslo in 1932 had written, “I have come to the conclusion that a good museum or gallery should be a place where people feel comfortable. If it stands in a garden or park, the visitors should be able to enjoy the beauty of the outdoors as a counterpoint to what is within”.

The successful design, by architect MUMA, readily meets this brief in a scheme which, whilst removing parts of the Scandinavian influenced interiors introduced by Bickerdike, develops the idea of connecting with the Park by including visual contact with the surrounding trees and landscape wherever possible. In particular the plan makes focal use of a fine plane tree which stands directly on the centre line of the existing building (the viewpoint of the illustration above). The application to the HLF was this time successful and after closing to allow the construction work to be completed, the Whitworth opened its extension into the Park, including a new landscape gallery, study rooms, learning centre and “cafe in the trees”, over the Valentine’s Day weekend in February 2015 to widespread media acclaim and with huge attendances. Sarah Price’s planting of the outside spaces in the sculpture court, art garden and orchard will be completed later in 2015. The new building has a greatly extended public area but is designed to use proportionately much less energy and this environmentally sensitive approach extends throughout the revived building, including to its new roofs which are sustainably planted to encourage wildlife.

Challenges and Opportunities. The renewed gallery, now called “the Whitworth”, opens at a time when the future of parks is in question. A report by the HLF in 2014 brought together a large body of evidence both in support of the beneficial contribution that parks can make to the education, health and wellbeing of ordinary people, but also of the threat of reduced capital spending, routine maintenance and disposal of parks by cash strapped local authorities unable to meet more than their statutory obligations. The HLF issued their report whilst other initiatives funded by them to “rethink parks” were ongoing. This programme has identified a number of projects where the management of individual parks across the country will be supported by initiatives geared towards producing private sector funding.

Manchester has since 2005 been considering this matter on a wider canvas through its review of the way it delivers services (Public Service Reform). In 2011 it abolished park services as a specialised unit and incorporated its functions in a directorate with those of 23 other services. Since then, under the continued pressure of reduced government funding, there have been two further re-organisations. The objective is to reduce demand for specialist and targeted services by “building the capacity within communities to build independent and thriving places” and by so doing drive down costs. The council is in the process of testing “different partnership models of delivering maintenance and investment strategies for parks, river valleys and open spaces to improve the standard of these spaces.”

It is not clear whether, or how, these new objectives relate to earlier strategies for parks and green spaces, adopted in 2001 and 2003, but the working and funding arrangements on which the hard worked-for Whitworth Park Management Plan was based no longer exist. The Friends are therefore working with the Whitworth to meet the objectives of the Plan in ways which are compatible with the council’s new ways of working and which will ensure the Parks development into the future.

KS 2014-12-29

Footnote: We are grateful to Bruce Anderson for permission to use many illustrations from his postcard collection. His website gives a more detailed commentary on the early history of the Park and in the context of Rusholme – Rusholme Archive

Many of the historical references have been gleaned from extensive Manchester Guardian reports on the development of the Park found in the Manchester Libraries Newspaper collection.